In the world of sculpture, the concept of composition extends far beyond the arrangement of shapes on a flat surface. It is the orchestration of volume, line, and void that invites viewers to move, pause, and re‑interpret the work from multiple angles. A sculptor must consider how mass interacts with the surrounding space, how a viewer’s eye is guided through depth, and how the tactile quality of material communicates rhythm and balance. This dynamic interplay is the heartbeat of sculptural composition, weaving together artistic intention and physical reality into a cohesive whole. Understanding composition in sculpture requires more than a grasp of basic geometry; it demands an intuitive sense of how form can occupy, expand, and contract within its environment. Throughout this discussion, the keyword “composition” will surface as a guiding principle that shapes every decision—from the initial sketch to the final polished surface.

Key Elements of Composition in Sculpture

Every sculptural piece is built upon a handful of core elements that dictate its visual and spatial resonance. First, the axis—whether horizontal, vertical, or diagonal—provides a structural backbone that aligns mass with intent. A strong axis can give a piece stability, while a subtle, ambiguous axis may evoke movement or tension. Second, balance must be achieved through careful placement of weight and negative space. Symmetrical balance offers a sense of calm, whereas asymmetrical balance challenges the viewer’s expectations, guiding the eye toward areas of heightened interest. Third, rhythm—repetition or alternation of forms—creates a visual beat that can lead the eye across the sculpture. Finally, the relationship between mass and void defines how the sculpture occupies space: does it fill a volume, carve it out, or leave it largely untouched? Mastering these elements allows the sculptor to craft a composition that feels both intentional and alive.

The Role of Space in Sculptural Composition

In sculpture, space is not merely an absence but an active participant. Positive space—the sculpted form—interacts with negative space—the gaps, channels, and openings that remain. This interplay determines how a piece feels in a room, how it responds to natural light, and how it engages viewers moving around it. A sculptor must contemplate the scale of the work in relation to its environment, ensuring that the composition neither overwhelms nor feels insignificant. The use of voids can create intrigue, allowing viewers to see the piece from within, while subtle perforations invite light to filter through, adding layers of depth. Moreover, the way a sculpture curves or angles away from the viewer can create a sense of motion, guiding the eye along a path that reveals different facets as the observer turns. Effective composition, therefore, balances the solid and the empty, crafting an experience that is both tangible and evocative.

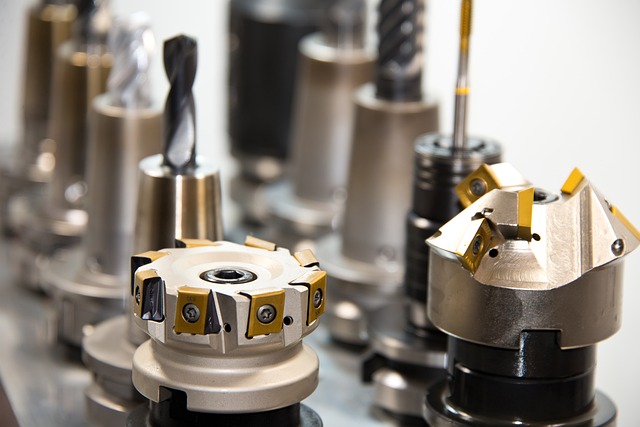

Materials and Form: Crafting Composition through Texture

Materials carry inherent qualities that influence composition. Clay offers pliability, allowing sculptors to experiment with fluid forms and intricate details before firing. Bronze provides permanence and the capacity for subtle tonal variations through patination, making it ideal for dynamic, kinetic compositions. Marble, with its translucence and hardness, invites the sculptor to play with light and shadow across polished surfaces. Each material demands a unique approach to mass distribution; for instance, stone requires careful consideration of internal support, while resin allows for translucent, layered constructs. The choice of material also informs the texture—the tactile surface that can be smooth, rough, or patterned—adding a sensory dimension to the composition. By harnessing the properties of material, sculptors can shape form in ways that enhance or subvert the intended spatial narrative, ensuring that every gesture contributes meaningfully to the overall composition.

Techniques for Enhancing Composition

- Modular Construction—building a sculpture from interconnected units allows for flexible arrangement, enabling the sculptor to re‑configure mass and void to refine balance and rhythm.

- Negative Space Sculpting—focusing on what is left unformed can yield surprising forms, where the absence becomes as significant as the presence.

- Light Interaction—designing openings, cuts, or reflective surfaces to manipulate how light moves across the sculpture, thereby accentuating depth and texture.

- Dynamic Angling—orienting the piece so that its strongest element faces the viewer or the most intimate angle encourages engagement and alters perceived scale.

- Scale Modulation—gradually increasing or decreasing size within a single piece can guide the eye along a compositional path, creating tension or release.

Conclusion: The Art of Balancing Form and Space

Composition in sculpture is a dialogue between tangible mass and the intangible void that surrounds it. By mastering the core elements—axis, balance, rhythm, and the dance of mass versus void—artists can sculpt experiences that resonate beyond the surface. Space becomes an active collaborator, while material and texture deepen the narrative, offering new layers of meaning with each interaction. Ultimately, successful composition invites viewers to inhabit the work, to feel its weight, to trace its lines, and to discover the unseen spaces that give the piece its full life. In sculptural practice, composition is not a static rule but an evolving principle that adapts to the artist’s vision, the chosen medium, and the ever‑changing context in which the sculpture exists. As sculptors continue to push the boundaries of form, the balance between mass and space will remain at the heart of their creative journey, offering endless possibilities for expression and connection.