When we think of sculpting, the image of a chisel gliding through stone or the steady rhythm of a mallet on clay often comes to mind. Yet there is a tool that is less romanticized but equally pivotal in the sculptural process: the hammer. Its presence in a studio is not merely functional; it is a symbol of intention, force, and the willingness to shape reality with a simple yet powerful implement. This article explores the humble hammer’s role in art, design, and the creative journey of a sculptor.

The Hammer as a Catalyst for Creative Exploration

In a sculptor’s workflow, the hammer is more than a finishing tool. It is a catalyst that invites experimentation. By striking a surface, the artist can discover unanticipated textures, reveal underlying layers, and create a dialogue between hardness and softness. Each blow is a question posed to the medium: “What lies beneath?” The hammer’s impact can uncover hidden forms, suggest new perspectives, and ultimately steer the direction of the piece.

- Testing the material’s response to impact reveals structural weaknesses and strengths.

- Unexpected dents and creases become intentional elements of composition.

- The rhythm of hammering can influence the emotional tone of the work.

Materials and the Hammer’s Touch

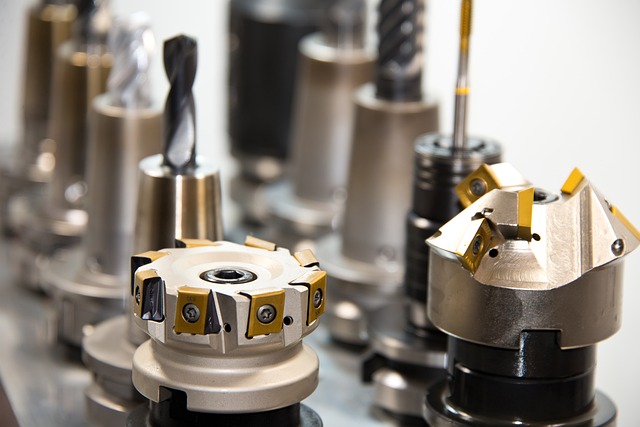

The choice of material—whether iron, bronze, steel, or a composite—determines how the hammer will interact. Iron, for example, can be pounded into a dense, expressive surface, while steel may require a lighter touch to avoid cracking. The hammer’s weight and shape are matched to the material’s properties, allowing the sculptor to control the force precisely. Mastery comes from understanding how a hammer translates kinetic energy into tangible changes.

“A hammer is a conduit for a sculptor’s intent, transforming an abstract idea into a tactile reality.”

Historical Perspectives: From Ancient Craftsmen to Contemporary Installations

Throughout history, the hammer has been a central tool in forging the world’s most iconic works. Ancient blacksmiths used hammers to create tools and weapons, laying the foundation for early sculpture. In the Renaissance, artists like Michelangelo employed hammers to carve marble, refining their masterpieces with a combination of precision chisels and decisive blows. In the 20th century, artists such as Pablo Picasso and Jeff Koons incorporated the hammer into their process, using it not only for construction but as a statement about labor and production.

Today, contemporary sculptors and designers continue to innovate with the hammer. Some use industrial hammers to create large-scale installations that mimic the look of a city’s infrastructure. Others employ specialized hammers with textured heads to produce complex surface patterns in metal or composite panels. In each case, the hammer remains a bridge between the artist’s vision and the physical world.

Techniques: From Punching to Pounding

There are several fundamental hammering techniques that sculptors employ:

- Punching – Applying concentrated force on a specific spot to create a dent or hollow. This technique is often used to simulate depth or to make a surface appear worn.

- Pounding – Delivering rhythmic blows over a broader area to smooth or texture the surface. Pounding can transform a flat panel into a landscape of subtle ripples.

- Chipping – Using a hammer with a chisel or wedge to remove small sections, refining details or correcting errors.

- Hitting for Alignment – Adjusting the orientation of a component by lightly tapping it into place, ensuring structural stability without compromising the design.

Design Considerations: Form, Function, and the Hammer’s Signature

When designing a sculpture, the hammer’s role is integrated from the outset. The sculptor must anticipate where force will be applied and plan for the resulting deformations. This foresight influences choices about scale, support structures, and material gradients. For instance, a piece that relies on hammered textures may include built-in bracing to counteract the stress points created during the process.

Beyond structural concerns, the hammer contributes to the aesthetic narrative. A hammered surface can evoke industrial resilience, organic growth, or abstract rhythm. By choosing a specific hammering pattern, the artist can guide the viewer’s eye, emphasizing certain edges or suggesting motion. In this way, the hammer becomes an expressive instrument, capable of conveying as much meaning as any brushstroke.

Case Studies: Hammer in Modern Sculpture

1. Steel Wire Sculpture – A contemporary artist used a small hammer to bend and twist steel wire into intricate spirals. Each strike softened the wire’s stiffness, allowing the form to settle into a fluid shape. The hammer’s repeated contact produced subtle ridges, giving the sculpture a tactile, almost musical quality.

2. Urban Collage Installation – A public art piece combined discarded metal panels with a heavy industrial hammer. The artist pounded the panels to create a rugged, weathered façade that mimicked the textures of city streets. The process highlighted the narrative of transformation and reclamation, using the hammer as both tool and metaphor.

Safety and Skill: Mastering the Hammer in Studio Practice

Working with a hammer, especially on large or brittle materials, requires rigorous safety practices. Protective gear, proper grip, and an understanding of material limits are essential. Skilled sculptors develop an intuitive feel for how much force to apply—too much can crack the work; too little may not achieve the desired effect.

Regular practice builds this intuition. Beginning with soft materials like foam or clay allows novices to experiment without fear of damaging expensive resources. As confidence grows, artists transition to harder substrates, gradually refining their technique.

Environmental Impact and Sustainable Practices

Modern sculptors increasingly consider the environmental footprint of their work. Hammers themselves are often made from durable steel, but their use can produce waste in the form of scrap metal or damaged materials. Sustainable approaches include:

- Recycling scrap metal back into new projects.

- Using reclaimed materials that already require minimal processing.

- Designing pieces that are modular, allowing for easier disassembly and reuse.

By integrating the hammer into a broader sustainability framework, artists can maintain artistic integrity while respecting ecological responsibilities.

Conclusion: The Hammer as an Artistic Voice

From the rhythmic pulse of a seasoned sculptor’s hand to the deliberate placement of a new piece, the hammer remains an essential, dynamic partner in creative expression. It bridges the gap between intention and material, translating abstract concepts into solid form. Whether shaping stone, bending metal, or inspiring design innovation, the hammer’s impact reverberates through the art world, reminding us that sometimes, the simplest tools can carry the greatest power.